Gospel of Thomas

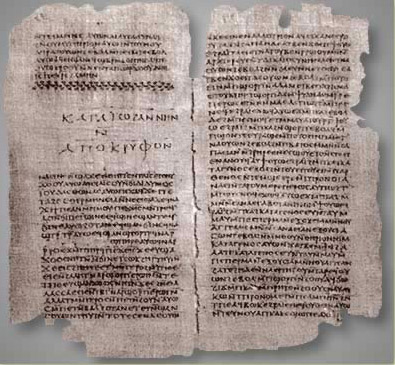

In 1945 two brothers were looking for fertiliser at the base of cliffs in the Egyptian region of Nag Hammadi. They found a huge earthen jar that contained twelve books bound in gazelle leather. These books are one of the most important archaeological finds of the twentieth century. Now known as the Nag Hammadi Library, they contained a complete manuscript of the Gospel of Thomas. It was one of fifty-two manuscripts in twelve books. The text was written in Coptic, the form of the Egyptian language spoken during later Roman imperial times.

In 1945 two brothers were looking for fertiliser at the base of cliffs in the Egyptian region of Nag Hammadi. They found a huge earthen jar that contained twelve books bound in gazelle leather. These books are one of the most important archaeological finds of the twentieth century. Now known as the Nag Hammadi Library, they contained a complete manuscript of the Gospel of Thomas. It was one of fifty-two manuscripts in twelve books. The text was written in Coptic, the form of the Egyptian language spoken during later Roman imperial times.

Scholars have been able to reconstruct the Gospel of Thomas in Greek, the probable original language of its original composition, although it possibly was originally written in Syriac or Aramaic.

Estimates of its date of origin range from 50 to 140 CE. It is not possible to attribute the authorship of the Gospel of Thomas to any particular sect with complete certainty. It has been published on the Internet. (http://www.gnosis.org/naghamm/gosthom.html).

It consists only of sayings of Jesus, 114 in all, in no particular order. Each saying is preceded by the phrase “And Jesus said.” Like “Q,” a hypothetical document that just may have contained some of Jesus’ original sayings, the Gospel of Thomas doesn’t refer to Jesus as “Christ,” “Lord,” or “Son of Man,” but simply as “Jesus.” Also, like Q, it lacks any mention of Jesus’ birth, baptism, miracles, travels, death, or resurrection. This is further evidence that suggests many of the details about Jesus’ life were made up by evangelical Gospel authors.

Thomas’ Jesus is depicted only as a human being. Jesus does not ask for subservience from his followers, but suggests they should try to discover their own true nature, which was a very “Gnostic” idea.

The Gospel of Thomas doesn’t list the canonical twelve apostles, although it does mention James, the brother of Jesus in saying number 12:

The Gospel of Thomas doesn’t list the canonical twelve apostles, although it does mention James, the brother of Jesus in saying number 12:

“The disciples said to Jesus, ‘We know that You will depart from us. Who is to be our leader?’ Jesus said to them, ‘Wherever you are, you are to go to James the righteous, for whose sake heaven and earth came into being.’”

If Jesus actually said this, it was a ringing endorsement of his brother! It is interesting that secular and church historians agree that a James, who was probably Jesus’ brother, took over the leadership of the Nazarenes after Jesus was killed. This James established himself in Jerusalem, and attracted a considerable following amongst Jews over the next twenty odd years. Like Jesus, he was a devout Jew, not a Christian. He was adamantly opposed to Paul, a pro-Gentile propagandist and a man intent on creating his own watered down version of Judaism. From James’ pro Jewish perspective, Gentiles were unwelcome foreigners in God’s holy land, (Israel) and Paul, with his stories about a pro-Roman son of God Christ, was nothing more than a heretic. It is ironic that Paul became the true founder of Christian theology, yet James, Jesus’ own brother, considered him an enemy.

The book of Acts claims that James sent Paul to the temple to be purified and prove he was a devout Jew, something Paul couldn’t do. He caused a racket, and was arrested for his own protection, and later transported back to Rome.

The book of Acts claims that James sent Paul to the temple to be purified and prove he was a devout Jew, something Paul couldn’t do. He caused a racket, and was arrested for his own protection, and later transported back to Rome.

James, Jesus’ brother, effectively terminated Paul’s missionary career. Jesus, if he had been alive, would have been very pleased.

Over half the sayings in Thomas are similar to sayings and parables found in the canonical Gospels, which suggests that Thomas is also based on the Q document, along with the gospels of Matthew and Luke. Some scholars have even speculated that Thomas may in fact be “Q.” Neither had any narrative connecting the various sayings, but rather than Q and Thomas being identical, it is more likely that the author of the Gospel of Thomas incorporated roughly the first two thirds of Q into his writing, not being aware of the final part of Q.

Conservative Christians today who happen to know about the Thomas Gospel consider it as an example of one of the early heresies and in opposition to the “real” church. Yet the reality is that Thomas may well have originated from sources much closer to Jesus than the gospel’s authors.

Why has there only ever been one copy of it found? Around 370 CE, the Archbishop of Alexandria, in Egypt, ordered the destruction of all “heretical” writings. Thomas’ Jesus did not support the orthodox story. An unknown individual or group obviously valued these sayings, so they were buried to prevent them being destroyed by the pyromaniacs of Christian orthodoxy. To destroy literature one does not like is not the conduct of people interested in the truth, but the behaviour of narrow-minded empire building bigots.

No one knows if there is a genuine connection between the gospel of Thomas and Jesus.

It can be argued that there are not any pearls of wisdom in Thomas. Its importance lies mainly in the sense that it proves there were people in early times who did not think Jesus was divine, and, if there is a real connection, Jesus himself was one of them.